Board Certified Forensic Document Examiner specializing in handwriting identification and suspect documents.

Emily J. Will, D-BFDE

Articles

These are a sample report, one of the many articles I have written over the years, and some Frequently Asked Questions.

An Anonymous Writing Case

In this case, comments were added to a document. Were they written by the same person who wrote the body of the document? The case was atypical because it focused on printed rather than cursive writing. Although there was not a large amount of writing, a conclusive opinion was possible. The Questioned Document is a photocopy of a government form. K1 refers to the known writing, and Q1,2 and 3 are the questioned writing.

Materials:

K1 - Known printed writing

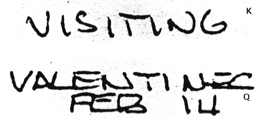

Q1 - Printed note written diagonally in the upper left corner of the QD

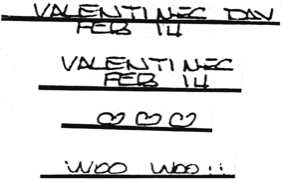

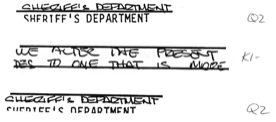

Q2 - Printed line "Sheriff's Department" written at top center of the QD

Q3 - Printed exclamation written diagonally in the upper right corner of the QD

Question: Were Q1, 2 and 3 written by the same person who wrote the known writing?

Procedures and Observations: All of the writing in this case was examined with the unaided eye and under microscope at magnifications from 7x through 25x. Glass alignment plates were used to examine the baseline, top line and spacing of the writing. The following writing characteristics are apparent:

In this case, comments were added to a document. Were they written by the same person who wrote the body of the document? The case was atypical because it focused on printed rather than cursive writing. Although there was not a large amount of writing, a conclusive opinion was possible. The Questioned Document is a photocopy of a government form. K1 refers to the known writing, and Q1,2 and 3 are the questioned writing.

Materials:

K1 - Known printed writing

Q1 - Printed note written diagonally in the upper left corner of the QD

Q2 - Printed line "Sheriff's Department" written at top center of the QD

Q3 - Printed exclamation written diagonally in the upper right corner of the QD

Question: Were Q1, 2 and 3 written by the same person who wrote the known writing?

Procedures and Observations: All of the writing in this case was examined with the unaided eye and under microscope at magnifications from 7x through 25x. Glass alignment plates were used to examine the baseline, top line and spacing of the writing. The following writing characteristics are apparent:

1. Both known and questioned writings use entirely upper case letters with the possible exception of the "I" which may not always be in the form of the capital. Although there is no dot over the I to indicate a lower case letter, the simple "stick" form of the "I" is used and it varies in height.

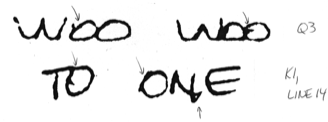

2. Letter spacing resembles elite or pica type in that it is non-proportional (every letter is given almost the same amount of horizontal space, regardless of its requirements). The result is open space around the "I" of "Valentines" and to a lesser extent the "I" of "Sheriff's" in the Q1 and Q2. This same spacing is seen in the words "visiting", "times" "inmates" and "special" in the known writing. Notice this letter spacing in the exhibit above. The top line is the known writing.

3. The baseline of Q1, Q2 and Q3 is artificially straight and appears to have been formed by holding a straightedge on the paper as a guide. Possibly this was done as a disguise factor. The bottoms of the letters "D", "B", "O", and others are complete, although flattened.

Therefore, the straightness of the baseline is not due to the bottom of the writing being clipped off with scissors in a cut and paste maneuver. The baseline of K1 is basically straight, although lacking in the precision shown in Q1-3. In the illustration (right) a glass plate containing an etched line has been placed on top of the questioned document and photographed to point out the straightness of the baseline and the flattened bottoms of the letters in Q1, 2 and 3.

4. The top lines are also quite straight, but are formed naturally by letters that are consistent in height. This is true in K1 and in Q1- 3. This exhibit shows top and bottom line straightness in K1 and Q2.

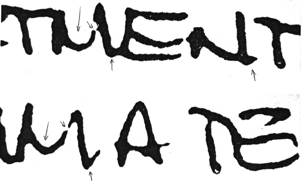

5. There is a small stroke toward the right at the end of many downward vertical strokes of letters such as "M", "N", "P", "T" and "H". This is obvious in the knowns, and even though Q1 - Q3 may have been formed against an artificial baseline, these strokes are evident in the "1" of "14" in Q1 and in the "P" and "M" of Q2. Notice this small stroke on the "M"s shown here. The top line is from Q2 and the bottom is from K1.

6. The "M"s show further evidence of identity in the shape and movement of the center curved stroke and the small hitch in the line which occurs in the same place in each writing. As further illustration of this characteristic the known and questioned writing have been optically overlaid and photographed through a comparison microscope. Color is achieved by using filters on the microcope's illuminators. The red is the questioned writing, the green is the known, and the black is where the two overlap.

7. The "O"s often join at the 9 or 10 o'clock position in both known and questioned writings. Notice this in the words "associated", "protracted", "to one", "more" and "off-peak" in the known writing and with the word "woo woo" in Q3.

8. The cross bar of the "A" and the buckle" of the "R" are positioned close to the baseline.

9. Although the writing is hand printed, there are connections from letter to letter and places where adjacent letters touch. This is a characteristic which could be more closely examined on the original document, but it is clear enough from the copy that this characteristic exists in both the known and questioned writing.

Conclusions: After a thorough examination of the questioned document, it is the examiner's opinion that the known writing (K1) and the questioned writing (Q1, Q2, and Q3) were written by the same person. All that remains is for the original to be produced to ascertain that the questioned material was actually written on that document, and not placed there mechanically.

Emily J. Will, D-BFDE, CDE

Forensic Document Examiner

The exhibits above were produced to illustrate mock trial testimony given in this case.

9. Although the writing is hand printed, there are connections from letter to letter and places where adjacent letters touch. This is a characteristic which could be more closely examined on the original document, but it is clear enough from the copy that this characteristic exists in both the known and questioned writing.

Conclusions: After a thorough examination of the questioned document, it is the examiner's opinion that the known writing (K1) and the questioned writing (Q1, Q2, and Q3) were written by the same person. All that remains is for the original to be produced to ascertain that the questioned material was actually written on that document, and not placed there mechanically.

Emily J. Will, D-BFDE, CDE

Forensic Document Examiner

The exhibits above were produced to illustrate mock trial testimony given in this case.

Good Standards in Document Examination Cases

by Emily Will, D-BFDE, CDE

by Emily Will, D-BFDE, CDE

This article is based upon the text of the article by the same name which was printed in the Trial Briefs, the quarterly publication of the North Carolina Academy of Trial Lawyers, in the 3rd Quarter of 1988. Some modifications to the text and format have been made.

In cases involving questioned documents, lawyers can take certain steps to ensure that the document examiner has the necessary materials to perform a thorough and conclusive examination. A questioned document examiner examines documents in cases where foul play is suspected. Cases frequently involve handwriting comparisons, typewriting comparisons, physical alterations to a document, and many variations on these themes. Some document examiners are involved with chemical testing of documents, while others concentrate on physical and mechanical testing. The document examiner is often a qualified expert witness, accepted in court by a judge after being examined and cross-examined by counsel.

The most important factor in any document examination is the quality of the standards (the documents of known origin that are compared with the questioned documents). The questioned document is important too, but it is a "given". It defines the outer limits of the examination, but how far the examiner can go within those limits depends on the standards.

Important Concepts re: Standard Documents

There must be no doubt about the authenticity of the standards. The document examiner needs to be able to rely on the standards, and the standards may need to be accepted as evidence in court.

Within the bounds of reason, there cannot be too many standards. Every handwriting shows natural variation. In cases where varying letter forms is an issue, if the examiner doesn't see enough standard writing, he or she will not have the information needed to form a good opinion. Typewriting cases often depend on identification of some individualizing defect of a machine. Defects can be sporadic, especially in their developmental stages. A few lines of typing or a quick run through the alphabet will not yield enough material to reveal the real character of the typing element.

The question arises, how much is enough? There is not an "across the board" answer. There are unusual cases where one or two signatures or a few typewritten lines will suffice. It all depends on the nature of the question. Be aware that in many cases the amount of standard material is an issue, and begin to amass samples early in the investigation. At the same time, realize that quantity is no substitute for quality, which will be discussed next.

Two Types of Standards

There are two types of standards: collected and requested. Collected standards are those already in existence that the attorney or investigator collects. They may be bank records, letters, legal forms, and the like. Requested standards are those that the subject is requested to give to facilitate the document examination.

The best standards are those that most closely emulate the timeframe, circumstances, materials and content of the questioned document. Therefore, look for collected standards executed close in time to the questioned document. This is especially critical in cases involving illness, death, accident, mental imbalance, substance abuse, or anything likely to cause a dramatic change in the subject's behavior.

There is a Method

Find out everything possible about the circumstances under which the questioned document was allegedly prepared. Was the subject lying sick in bed, standing at a counter, holding a clipboard in his or her lap? Try to obtain standards written under similar conditions.

Is the questioned document a check, letter, legal form, passport? Is it written on blank paper, lined paper, graph paper, cardboard? Was pencil, ballpoint, felt tip or fountain pen used? If there was anything unusual about the materials of the questioned document, try to duplicate that uniqueness in the standards.

Content can be important in a document examination. Look for collected standards that share letter combinations, words, phrases or numbers with the questioned document. When requesting standards prepare a text that will include such similar content.

There is a method for obtaining good requested standards. In a handwriting case the material to be written should be dictated to the subject, rather than copied by the subject. Prepare the text and assemble the proper materials. Have on hand blank paper and any necessary forms and a selection of writing instruments. The subject may provide a pen or pencil and should be allowed to use it for the first writing sample.

Have the subject do some free writing to loosen up. Then dictate the material at a reasonable speed. Do not give any help with spelling or punctuation. Have the subject sign and date the sample. Take the sample and set it aside out of view. After some general conversation, ask the subject to repeat the task. This is a good time to request that the subject use a different paper or writing instrument if appropriate. Dictate a bit faster the second time. More repetitions may or may not be needed.

If you are especially interested in standard signatures, prepare several forms or blanks with the same layout as the questioned document for the subject to sign. Have the subject sign these forms one at a time. A column of signatures on a single sheet of paper may be useful if it appears in conjunction with several other types of standards, but by itself is not the best standard for examination. A column of ten signatures written this way tends to become ten copies of one signature rather than ten distinct signatures.

Depending on the questioned document, it may be important to request that the subject write in printed or cursive form. Also, it may be necessary to request samples written with the unaccustomed ("wrong") hand.

Number the samples so that the document examiner will be aware of the order of things, and keep a separate anecdotal record of anything unusual that happens during the session.

Handle all documents carefully. Do not fold documents - even those already folded. Repeated folding and unfolding of documents can cause damage and obscure that which needs to be examined. The best way to handle, transport and store documents is unfolded and in archivally safe covers away from strong light and moisture. If any change is made to a document (staples removed, an accidental tear, etc) a note should be made (but not on the document).

Document examinations often begin with, and even end with, photocopies. When possible, keep track of the generation of any copy made. With each successive copy some loss of detail and addition of superfluous markings can occur. Sometimes a good opinion can be formed based on photocopies and sometimes it cannot. Of course, originals are always preferred.

Unless attorneys have been involved in a questioned document case they often have no reason to think of the necessary precautions. Each point made here can be expanded and taken in several directions. The best way to assure good results is to contact the document examiner early in the investigation and work with the examiner to plan an approach to the specific case.

This article is based upon the author's experience and borrows heavily from the following works:

1. Hilton, Ordway, Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents, refised edition, Elsevier Series in Forensic Science, N.Y., 1984

2. Osborn, Albert S., Questioned Documents, Second Edition, Patterson Smith, Montclair, NJ, 1929

In cases involving questioned documents, lawyers can take certain steps to ensure that the document examiner has the necessary materials to perform a thorough and conclusive examination. A questioned document examiner examines documents in cases where foul play is suspected. Cases frequently involve handwriting comparisons, typewriting comparisons, physical alterations to a document, and many variations on these themes. Some document examiners are involved with chemical testing of documents, while others concentrate on physical and mechanical testing. The document examiner is often a qualified expert witness, accepted in court by a judge after being examined and cross-examined by counsel.

The most important factor in any document examination is the quality of the standards (the documents of known origin that are compared with the questioned documents). The questioned document is important too, but it is a "given". It defines the outer limits of the examination, but how far the examiner can go within those limits depends on the standards.

Important Concepts re: Standard Documents

There must be no doubt about the authenticity of the standards. The document examiner needs to be able to rely on the standards, and the standards may need to be accepted as evidence in court.

Within the bounds of reason, there cannot be too many standards. Every handwriting shows natural variation. In cases where varying letter forms is an issue, if the examiner doesn't see enough standard writing, he or she will not have the information needed to form a good opinion. Typewriting cases often depend on identification of some individualizing defect of a machine. Defects can be sporadic, especially in their developmental stages. A few lines of typing or a quick run through the alphabet will not yield enough material to reveal the real character of the typing element.

The question arises, how much is enough? There is not an "across the board" answer. There are unusual cases where one or two signatures or a few typewritten lines will suffice. It all depends on the nature of the question. Be aware that in many cases the amount of standard material is an issue, and begin to amass samples early in the investigation. At the same time, realize that quantity is no substitute for quality, which will be discussed next.

Two Types of Standards

There are two types of standards: collected and requested. Collected standards are those already in existence that the attorney or investigator collects. They may be bank records, letters, legal forms, and the like. Requested standards are those that the subject is requested to give to facilitate the document examination.

The best standards are those that most closely emulate the timeframe, circumstances, materials and content of the questioned document. Therefore, look for collected standards executed close in time to the questioned document. This is especially critical in cases involving illness, death, accident, mental imbalance, substance abuse, or anything likely to cause a dramatic change in the subject's behavior.

There is a Method

Find out everything possible about the circumstances under which the questioned document was allegedly prepared. Was the subject lying sick in bed, standing at a counter, holding a clipboard in his or her lap? Try to obtain standards written under similar conditions.

Is the questioned document a check, letter, legal form, passport? Is it written on blank paper, lined paper, graph paper, cardboard? Was pencil, ballpoint, felt tip or fountain pen used? If there was anything unusual about the materials of the questioned document, try to duplicate that uniqueness in the standards.

Content can be important in a document examination. Look for collected standards that share letter combinations, words, phrases or numbers with the questioned document. When requesting standards prepare a text that will include such similar content.

There is a method for obtaining good requested standards. In a handwriting case the material to be written should be dictated to the subject, rather than copied by the subject. Prepare the text and assemble the proper materials. Have on hand blank paper and any necessary forms and a selection of writing instruments. The subject may provide a pen or pencil and should be allowed to use it for the first writing sample.

Have the subject do some free writing to loosen up. Then dictate the material at a reasonable speed. Do not give any help with spelling or punctuation. Have the subject sign and date the sample. Take the sample and set it aside out of view. After some general conversation, ask the subject to repeat the task. This is a good time to request that the subject use a different paper or writing instrument if appropriate. Dictate a bit faster the second time. More repetitions may or may not be needed.

If you are especially interested in standard signatures, prepare several forms or blanks with the same layout as the questioned document for the subject to sign. Have the subject sign these forms one at a time. A column of signatures on a single sheet of paper may be useful if it appears in conjunction with several other types of standards, but by itself is not the best standard for examination. A column of ten signatures written this way tends to become ten copies of one signature rather than ten distinct signatures.

Depending on the questioned document, it may be important to request that the subject write in printed or cursive form. Also, it may be necessary to request samples written with the unaccustomed ("wrong") hand.

Number the samples so that the document examiner will be aware of the order of things, and keep a separate anecdotal record of anything unusual that happens during the session.

Handle all documents carefully. Do not fold documents - even those already folded. Repeated folding and unfolding of documents can cause damage and obscure that which needs to be examined. The best way to handle, transport and store documents is unfolded and in archivally safe covers away from strong light and moisture. If any change is made to a document (staples removed, an accidental tear, etc) a note should be made (but not on the document).

Document examinations often begin with, and even end with, photocopies. When possible, keep track of the generation of any copy made. With each successive copy some loss of detail and addition of superfluous markings can occur. Sometimes a good opinion can be formed based on photocopies and sometimes it cannot. Of course, originals are always preferred.

Unless attorneys have been involved in a questioned document case they often have no reason to think of the necessary precautions. Each point made here can be expanded and taken in several directions. The best way to assure good results is to contact the document examiner early in the investigation and work with the examiner to plan an approach to the specific case.

This article is based upon the author's experience and borrows heavily from the following works:

1. Hilton, Ordway, Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents, refised edition, Elsevier Series in Forensic Science, N.Y., 1984

2. Osborn, Albert S., Questioned Documents, Second Edition, Patterson Smith, Montclair, NJ, 1929

Q.

Can you describe an individual's personality from examining handwriting?

A.

No, forensic document examination does not develop information about personality. There is a separate field of study called "Graphology" which deals with personality and handwriting.

Q.

Can right or left handedness be detected by examining handwriting?

A.

Contrary to popular belief, there are three things that can not be reliably ascertained by examining handwriting. One of those is the "handedness" of the writer. The other two things are the author's gender and age.

Q.

Can you compare printed writing to cursive writing?

A.

Rarely. Some writers style of writing is a mix of cursive and printed forms, thereby allowing the examiner to carry out some level of examination on either cursive or printed writing. There are also many factors other than letter formation that enter into the examination and and analysis process. However, it is generally accepted that the materials to be compared need to be written in the same style: cursive to cursive, hand printing to hand printing, upper case to upper case, lower case to lower case, and one of the first steps in methodology is to determine that the materials provided are indeed comparable according to this principle.

Q.

Can you examine documents in a foreign language?

A.

Yes, it is possible, but the examiner must first learn about the characteristics of the written language and how that writing is taught. For example, in some languages, placement of diacriticals (distinguishing strokes) is important, and in other languages, shading of handwritten strokes is significant. The actual methods of examination are the same, but factors are weighed differently when the structure of the writing varies among languages.

Q.

Can a document examiner work with photocopies of questioned documents?

A.

This question must be answered on a case by case basis. If the copy is of good quality, and if there is enough information in the writing to allow an opinion, a copy can be sufficient. But there are some situations where the opinion rests on a subtle aspect of the writing that might only be visible on an original viewed under the microscope. In such situations, examination of the original is critical. Often the examiner's opinion must be qualified due to limitations on the examination process due to submission of non-original documents.

Q.

Can a client fax documents to you for examination?

A.

There is a wide range in reproduction quality of faxed documents. Until recently a faxed document was of minimal use for comparison of handwriting. The fax process could digitize the writing line, obscure details, and add flaws to the document. A large number of fax machines still produce poor quality documents. However, there are now higher quality fax machines, and there is also a process of electronic faxing in which a document is scanned and transmitted to a virtual fax number through the internet. As a result there are some faxed documents of improved clarity and containing more detail. It is best to evaluate faxed documents on a case-by-case basis. Of course, there are document questions about the faxing process itself, but those are best handled by examination of the actual faxed documents rather than a fax of the fax.

Inferring Relative Speed of Handwriting from the Static Trace - Journal of Forensic Document Examination - Vol.22, 2012

Progress in Digital Microscopy - A Technical Review of the MiScope Digital Microscope - Journal of Forensic Document Examination - Vol. 20, 2010

Micrometry Using a Calibrated Ocular Reticule; co-author with Joseph Barabe, Senior Microscopist, NADE Journal, 2005

Wake Up to the Wacom™ Tablet - Journal of Forensic Document Examination –Vol. 17, 2004-5

Seeing is Believing – Exhibits from the Perspective of the Forensic Document Examiner, Illinois Law Enforcement Executive Forum, Vol. 2, #3, August, 2002

Handwriting, Biomechanics and Significance: Concepts in Handwriting Identification, NADE Journal, Summer 2001

The Microscope - Through the Looking Glass - Chemistry in Australia - (The Journal of the Royal Society of Chemists in Australia) May 2000

Ink Differentiation with Digital Photography, NADE Journal, Spring, 1999 and International Journal of Forensic Document Examination. 1999

A Discussion of Dandy Rolls and Watermarks - co-author Mr. Robert Johnson , NADE Journal, Fall, 1999

Good Standards in Document Examination Cases, Trial Briefs (North Carolina Academy of Trial Lawyers) Summer, 1988

Medical Records Case Solved Photographically, NADE Journal, Spring, 1998

Progress in Digital Microscopy - A Technical Review of the MiScope Digital Microscope - Journal of Forensic Document Examination - Vol. 20, 2010

Micrometry Using a Calibrated Ocular Reticule; co-author with Joseph Barabe, Senior Microscopist, NADE Journal, 2005

Wake Up to the Wacom™ Tablet - Journal of Forensic Document Examination –Vol. 17, 2004-5

Seeing is Believing – Exhibits from the Perspective of the Forensic Document Examiner, Illinois Law Enforcement Executive Forum, Vol. 2, #3, August, 2002

Handwriting, Biomechanics and Significance: Concepts in Handwriting Identification, NADE Journal, Summer 2001

The Microscope - Through the Looking Glass - Chemistry in Australia - (The Journal of the Royal Society of Chemists in Australia) May 2000

Ink Differentiation with Digital Photography, NADE Journal, Spring, 1999 and International Journal of Forensic Document Examination. 1999

A Discussion of Dandy Rolls and Watermarks - co-author Mr. Robert Johnson , NADE Journal, Fall, 1999

Good Standards in Document Examination Cases, Trial Briefs (North Carolina Academy of Trial Lawyers) Summer, 1988

Medical Records Case Solved Photographically, NADE Journal, Spring, 1998